By now, you’ve probably heard that there is a monkeypox outbreak traveling around the globe. Cases have spread far and wide, including in the US, Canada, Europe, and Australia. It’s the largest outbreak ever recorded outside of western and central Africa, where monkeypox is common.

But controlling this outbreak demands preventive measures, such as avoiding close contact with people who have the illness and vaccination. One method of vaccination, called ring vaccination, has worked well in the past to contain smallpox and Ebola outbreaks. It may be effective for monkeypox as well.

How can monkeypox be contained?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization, monkeypox is unlikely to become a pandemic. At this time, the threat to the general public is not high. The focus is on identifying possible cases and containing the outbreak as soon as possible.

Three important steps can help stop this outbreak:

- Recognize early symptoms

- Usually, early symptoms are flulike, including fever, fatigue, headache, and enlarged lymph nodes.

- A rash appears a few days later, changing over a week or two from small flat spots to tiny blisters similar to chickenpox, then to larger, pus-filled blisters.

- The rash often starts on the face and then appears on the palms, arms, legs, and other parts of the body. If monkeypox is spread by sexual contact, the rash may show up first on or near the genitals.

- Take steps to stop the spread

- Monkeypox spreads through respiratory droplets or by contact with fluid from skin sores.

- Anyone who has been diagnosed with monkeypox, or who suspects they might have it, should avoid close contact with others. Once the sores scab over, the infected person is no longer contagious.

- Health care workers and other caregivers should wear standard infection control gear, including gloves and a mask.

- In the current outbreak, many cases began with sores in the genital and rectal areas among men who have sex with men, so doctors suspect sexual contact spread the infection. As a result, experts are encouraging abstinence when monkeypox is suspected or confirmed.

- Use vaccination to help break the chain

- Monkeypox is closely related to smallpox. People who received a smallpox vaccine in the past may have some protection from monkeypox. (The US smallpox vaccination program was discontinued in 1972, and smallpox was declared eradicated worldwide in 1980.)

- Stockpiled smallpox vaccinations and newer vaccines that can be used for monkeypox or smallpox are also available.

Ring vaccination

Monkeypox differs from the virus that causes COVID-19. People with monkeypox usually have symptoms when they’re contagious, and the number of infected persons is usually limited.

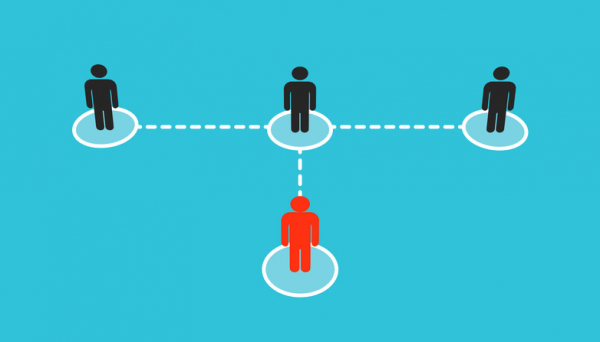

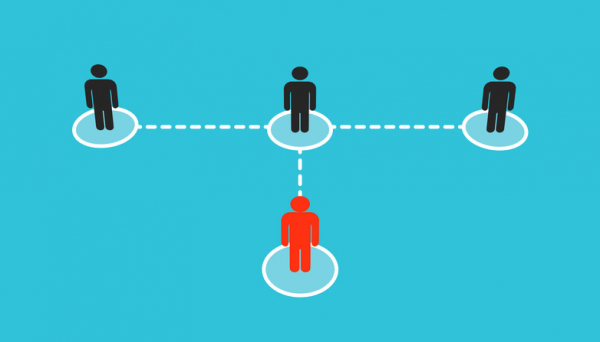

This means it’s possible to vaccinate a “ring” of people around them rather than vaccinating an entire population. This selective approach is called ring vaccination.

Ring vaccination has been used successfully to contain smallpox and Ebola outbreaks. It may come in handy for monkeypox as well. Here’s how it works:

- As soon as a case of monkeypox is suspected or confirmed, the patient and their close contacts are interviewed to identify possible exposures.

- Vaccination is offered to all close contacts.

- Vaccination is also offered to those who had close contact with the infected person’s contacts.

Ideally, people should be vaccinated within four days of exposure.

This approach requires widespread awareness of monkeypox, rapid isolation of suspected cases, and an efficient contact tracing system. And of course, vaccines must be available whenever and wherever new cases arise.

Are the vaccines used for monkeypox effective?

According to the CDC, the smallpox vaccine is 85% effective against monkeypox.

While a newer vaccine (JYNNEOS) directed against monkeypox and smallpox has only been tested for effectiveness in animals, it is also expected to be highly effective in humans.

Of course, vaccinations can only work if people are willing to receive them. We’ll learn more about this as more people are offered the option for vaccination.

Are the vaccines used for monkeypox safe?

As with most vaccines, the most common side effects include

- sore or itchy arm at the site of the injection

- mild allergic reactions

- mild fever or fatigue.

Fortunately, more severe side effects, such as significant allergic reactions, are rare.

The bottom line

In light of the current monkeypox outbreak, you may soon be hearing more about ring vaccination. Then again, if appropriate measures are taken to prevent its spread, this outbreak may soon be over. Either way, this won’t be the last time an unusual virus shows up seemingly out of the blue in unexpected places. Climate change, shrinking animal habitats, rising global animal trade, and increasing international travel mean that it’s only a matter of time before this happens again.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. … See Full Bio View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD